This recipe is derived from Veal picata! However this has neither veal nor capers! It is a creamy chicken pasta, easy to make and interestingly different. Here we honor a LGBT hero who worked hard for gay Asians and Pacific Islanders. Read a short story about George Choy after the recipe.

In the place of seldom used capers, here we rely on the flavors of lemon, thyme, and dried cranberries! Try this beautiful meal on your table.

Ingredients:

1 Tbs olive oil

About 1 and a half Lbs boneless skinless chicken, cut into bite-size pieces

¼ tsp each: Salt & pepper

2 tsp. finely chopped garlic

3 cups chicken broth (no salt added)

2 tsp. grated lemon peel and 2 Tbs lemon juice (from 1 large lemon)

8 oz uncooked pasta, here I used tri colored bowties

¼ cup craisans &

1 tsp fresh thyme leaves, crushed

½ cup non fat half & half

Chopped parsley, if desired

Directions:

Do your cutting: cut up chicken into 1-2 inch pieces. Mince the garlic. Then with your fingers, rub the leaves off of the thyme with a stroke from tip to base.

In 4-quart Dutch oven, heat olive oil over medium-high heat. Season chicken with salt and pepper; cook 5 to 7 minutes, stirring frequently, until chicken is no longer pink.

Add garlic; cook 30 to 60 seconds, stirring constantly, until fragrant.

Add chicken broth, lemon juice, and pasta; heat to boiling.

Place the thyme leaves in your palm and crush with thumb, then add.

Reduce heat to medium; simmer 10 to 12 minutes, stirring occasionally, until most of liquid is absorbed and pasta is al dente.

Cooking the pasta in the pot with cause the sauce to thicken.

Stir in the half & half; cook just until heated through.

Stir in grated lemon peel; serve warm.

Garnish with parsley.

Can can add lemon zest and stir in grated Parmesan cheese at the end.

What a beautiful meal to present. Add a green vegetable if you wish.

For our music: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K1b8AhIsSYQ

So proud of My Master Indy!

socialslave

To satisfy and restore.

To nourish, support and maintain.

To gratify, spoil, comfort and please,

to nurture, assist, and sustain

…..I cook!

Please buy slave's cookbook:

The Little Black Book of Indiscreet Recipes by Dan White http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00F315Y4I/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_vAT4sb0934RTM via @amazon

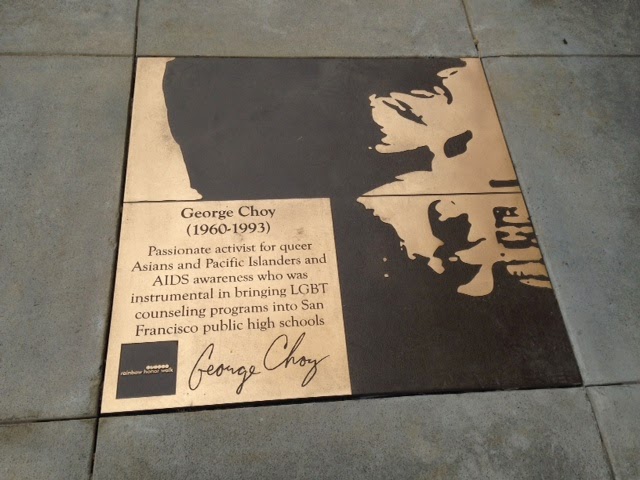

George Choy

George Choy was a passionate advocate of civil and human rights for LGBTQ communities of San Francisco and around the world. He believed that we are “part of the family, too.” Choy became “a constant supportive presence who delivered with action, an activist impatient with injustice, but who nevertheless possessed the rare gift of forgiving.”

Being born on February 6, 1960, Choy described himself as an “Acqueerian”. He realized and accepted his homosexuality during the summer after he graduated from San Francisco’s Mission High School. Instead of feeling guilty, “instead of lying to myself and others,” he told himself to “be happy and love who[m] you want.”

His insight and perception were transformative. “I was free,” he wrote later. “I no longer hid from my straight schoolmates about my sexuality.” He told his two closest friends, hoping they would “support me.” Both did. He was best man at their weddings, and they remained lifelong confidants.

Choy grew up in Chinatown, across the street from the International Hotel. He saw the need for activism early on. His home was in what was once the heart of San Francisco’s Philippine community. The Filipino seniors who lived there were forcibly evicted for an “urban renewal” project during the 1970s. Their protests to save their homes and preserve their community left an indelible impression on him. This area was about ten blocks of low-cost housing, stores, restaurants, markets, and other businesses that supported a neighborhood of some 10,000 people.

Believing that we belong to a larger world than described by our ethnic, religious, or social identifications, Choy wanted to make connections across these artificial barriers to show our common humanity. Choy was especially committed to achieving full civil and human rights for LGBTQ Asians, he became an early and active member of San Francisco’s Gay Asian Pacific Alliance (GAPA).

Choy also supported queer youth—an often neglected, a minority within a minority. In the Spring of 1990, he was asked to lead GAPA’s effort to pass Project 10, a measure to provide much-needed counseling services for San Francisco’s LGBTQ public school students. He knew that there were still “those who experienced gay-related violence,” including some “attacked by family members because of their sexuality.”

The proposal faced opposition. It was claimed that it was either unnecessary or inappropriate, or not fundable. Choy, however, stressed its importance for all students, especially for Gay Asians. “We have to be there,” he said, “to make sure they know that there are Gay Asians.” “They” included not only members of the school board and the mostly white gay activists who supported the proposal, but it also included Asian Christian fundamentalists, who had come out in full force against the measure, arguing the service was not needed because there were “no gay Asians.”

During the critical meeting on the proposal, Choy made an impassioned plea for it to pass. He argued that Gay Asians were “not to be taken for granted,” but to be “loved, saved, and protected.” In May 1990, the Board of Education decided unanimously to implement Project 10 the following September. “This program,” said Kevin Gogin, the first counselor hired, “will send a message that all people are important, no matter who they are.”

Choy’s campaign supporting civil rights for gay Asians went far beyond San Francisco. In 1991, GAPA supported a lawsuit against a public youth activity center in Tokyo, which denied the use of its facilities to OCCUR, a local LGBTQ organization. When members of OCCUR visited San Francisco to gain support for their anti-discrimination case against the Japanise government, Choy became their point person. He organized press conferences, held meetings, and got local political figures involved.

Then he traveled to Japan to speak about human rights for gays to large audiences in Tokyo and Osaka, one of San Francisco’s sister cities. Choy was a passionate advocate of civil and human rights for members of the LGBTQ communities of San Francisco and around the world. Driven by the belief that we are “part of the family, too,” he became “a constant supportive presence who delivered with action, an activist impatient with injustice, but who nevertheless possessed the rare gift of forgiving.”

At the same time, Choy became the Community HIV Project Liaison for GAPA. He was the outreach coordinator for the GAPA Community Health Project, which provided direct support services to gay Asians and Pacific Islanders. His efforts included prevention, education, early intervention, HIV case management, emotional and practical support, and direct care. He also was an active and ardent member of ACT UP. More than anything else, he showed what a single individual can do for the benefit of us all.

Choy passed from complications of HIV in1993.

Choy often spoke of what he had learned since that summer after high school. “Deep inside each of us,” he told his audiences, “burns a special flame…which other people misunderstand…But we, as gay and lesbian people, understand…that we have a special capacity to love one another. We understand that this love is real and valid. We understand that this special flame will light the way for us…Continue to fan the flame, strong, proud, and just.”

Choy was among the inaugural twenty honored with a bronze plaque in San Francisco's rainbow Honor Walk.

We are proud of you George!